Brampton Brick has more than 100 years of history in Canada and recently opened its first manufacturing facility in the United States. Keith Regan learns from the company’s new vice president of strategic planning how the company plans to use diversification along with a continued emphasis on quality and service to pave the way for future growth.

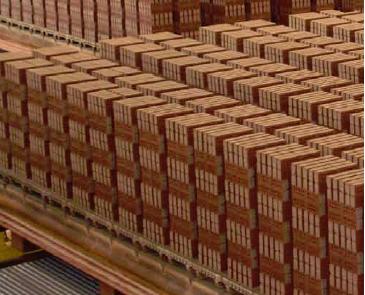

A century ago, Brampton Brick was producing bricks at its Ontario plant, a facility that today, thanks to repeated expansions and significant investment in automation, has the capacity to be the largest single brick-making facility in North America, capable of producing 300 million bricks and brick equivalents each year. In 2008 Brampton opened a second manufacturing facility in Farmersburg, Indiana, a fully automated plant capable of producing 100 million modular blocks annually.

The production capacity and experience is part of the foundation of a strategic growth plan for Brampton Brick, one that includes diversification into concrete-based products such as landscape pavers and architectural accent pieces as well as a continued focus on operational excellence that will allow it to maintain high standards for quality and customer service.

“Our strategy going forward is all focused on growth,” says Frank Buck, senior vice president of strategic planning at Brampton. Buck joined the company late in 2009 after a decade with a competitor. “We’re looking at a diversification strategy to help us do that, and over time we’ll become more of a masonry products business that provides a full array of concrete-based products as well as clay brick products. We want to grow our share of the wall out there.”

That wall includes a range of landscape and building settings, from residential and commercial to high-end institutional buildings—especially in the growing healthcare sector—where architects are increasingly embracing new products to add color and interest to buildings and also to help buildings earn LEED points as green buildings. “If you look at the greening of North America and the greening of construction industry products,” says Buck, “everyone is very interested in being able to qualify for LEED points, and there is a lot happening around recycled and reclaimed products and also about how well exterior materials perform in terms of energy efficiency.”

Brampton Brick’s geographic footprint includes large swaths of both Canada and the US, where it serviced the construction market even before it opened a US manufacturing facility. The weight of its products and the high cost of transporting them limits its range somewhat, though on some higher-end products, the margins are robust enough to enable shipping to markets such as New York City.

The competitive marketplace, meanwhile, is crowded, and one of the challenges Brampton faces is to cut through the clutter. While there are fewer companies with the capabilities to make the range of specialty products Brampton offers, a typical distributor may carry bricks from as many as 20 different manufacturers. “Coming out of this recession, there will likely be fewer, but a lot of dealers carry many of the brick lines,” Buck says.

Brampton has long sought to distinguish itself on quality and service. “There’s no point in having great products if you don’t have the service to stand behind them,” Buck adds. “You have to back up quality with service. That means delivering the right product on time and being innovative in terms of size, color and texture.” Innovations include through-body colors instead of painted-on surface color, for instance.

Brampton spends a lot of time and resources ensuring it is getting the most out of the costs it puts into its product and supply chain. “You have to be competitive on price, and at the end of the day that means being sharp on costs,” Buck says.

That means trying to reduce the two largest costs a brick-maker faces: labor and fuel. Clay brick-making, in particular, is a “very punishing process” that requires a lot of fuel to create very high temperatures in the kiln over a long time. “We’ve done a lot of experimenting with using different types of gases to fuel our plants, be it methane or pet coke or propane,” Buck explains. “You’ve got to manage your kiln properly, and that means a lot of maintenance to make sure there are no leaks and that your burners and valves are running as efficiently as possible.”

The industry has also embraced automation as a way of reducing labor costs. Traditionally, clay brick-making has been a labor-intensive process, with bricks having to be bundled before they are placed in the kiln and again when they are done being fired. “The old days of having 100-plus people working in a brick plant doesn’t work in this marketplace.”

In fact, Brampton’s Farmersburg facility is “as modern as any you’ll find in the world today,” Buck states. Up and running just over a year now, the plant is fully computerized and automated, with the facility capable of being run by as few as a dozen workers, a number that would likely only double even if output was boosted by adding additional shifts when the market warrants.

Brampton also invests heavily in quality assurance, continually taking products out of production and testing them to ensure they meet relevant North American standards, which in turns helps it meet code requirements when used in construction settings. The company also employs a ceramics engineer who works with a team of people who are dedicated to testing and checking the recipes and formulations used to make the finished product.

Managing the flow of production is another challenge, with Brampton making the 20 percent of its inventory that makes up 80 percent of its sales for inventory while also making other products to order. To help make that possible, Brampton relies on its field sales representatives to keep up to speed on the status of building projects for which it may be asked to bid on providing product. “It’s a dynamic process,” Buck says. “You need to have sales reps in place who can provide a lot of market intelligence and have great relationships with contractors to make sure we’re in the loop and have good advance knowledge of when a contract might be coming onto the market.”

The economic slowdown and the construction recession in particular have hit the brick business hard. Residential housing uses the vast majority of brick and related products, and that market may remain depressed for the foreseeable future. “We’re using this time to do the up-front missionary work and let people know that we’re on the ground in the US now with clay bricks and concrete masonry products ready to service that market.”http://www.bramptonbrick.com